After ten months on the ground in Asia, we thought we'd seen it all. After bizarre Hindu festivals, soaring Tibetan monasteries, steaming Laotian jungles and Chinese breakfast buffets, we were surely ready for anything. We hadn't counted on Turkmenistan.

Sure, we knew a few things about the country. From 1991 until 2006, Turkmenistan was ruled by one of the world's truly great lunatics. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, a lackluster communist functionary named Saparmurat Niyazov seized his chance for immortal glory by declaring himself the Great Turkmenbashi, Leader of All Turkmen, and President for Life of the newly independent nation. After the mandatory 'all dissidents mysteriously vanish' phase of the power grab, Great Turkmenbashi got down to the serious business of erecting golden statues of himself all over the country, officially re-naming the month of April after his mother, and copyrighting the Turkmen alphabet. After the Turkmenbashi's death in 2006, the country is now in the capable hands of a guy rumored to be the great leader's illegitimate son. We'd been warned that the banks didn't function, there was no internet access, most of the country was a scorched desert wasteland, and government agents would follow us everywhere we went. Naturally, we decided to check the place out.

Although we've come to love independent travel, a guide is required at all times for foreigners in Turkmenistan. Fortunately, ours proved to be outstanding. Dima (short for Dimitri) met us as we cleared the border, a hulking Russian in a gleaming golden jeep. Within minutes, he and Mike were howling with laughter in the front seat, trading dry Soviet-style jokes about the government road system (in Turkmenistan, the road drives YOU...). Happily, Susannah was too busy swooning over the jeep's air conditioning to reflect on her husband's idiocy.

Our first stop was the ruins of Konye-Urgench, a former silk road Khanate now largely buried beneath the dunes. In modern times, it has become a holy place where the people of the vast Karakum Desert come to make offering and seek answers. The local religion is a unique and timeless mix of Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Animism and Islam. Women build intricate cradles of wood and yarn, then leave them on holy sites to petition Allah and their ancestors for a child. While we were there, a young man climbed an ancient burial mound, where bleached white skulls and bones still protrude from the earth, and then rolled down the slope past a lone stick in the ground covered in prayer offerings. In his case, rolling to the right of the 'sacred tree' meant Allah wanted him to go to college - left was for early marriage and taking over his father's goat herd. He went right, and witnesses seemed sure he'd given himself a discreet push in that direction.

The Sacred Tree of Konye-Urgench

As our golden jeep pulled away from the ruined city, Dima gleefully informed us we were headed south, into the vastness of the Karakum Desert, to camp at a place he called 'the crater.' He refused to tell us more, only that it was a 'volcano in the desert,' and we could not leave the country without seeing it. We drove for hours on a bad road through the desert, passing only camels and the occasional shack, before we stopped for mutton pancakes at a lonely desert cafe with a few old tables and a golden bust of the Turkmenbashi. Finally, hours later, we veered off the road and across the dunes in the dwindling light. As our golden jeep climbed the final rise, Dima triumphantly exclaimed "... and now... the crater!"

The landscape before us was lit in a fiery glow. At its center was a huge, flaming hole in the ground. The blazing pits of hell... A horrific inferno... We ran down for a closer look.

What was a flaming crater doing in the middle of the desert? All Dima could tell us, and all anyone seems to know, is that the Soviets were here looking for natural gas in the sixties, there's nobody at all here now, and the crater the Ruskies left is still on fire forty years later. Chalk another one up for Lenin and his Worker's Paradise. After dinner and the requisite shots of vodka (Russians in the desert are still Russians, after all), Dima tucked us in with a warning about the local fauna. "We have the cobra here, and also we have many spider, but no worry. Spider just paralyze you, only death for maybe six percent of time. If cobra bite, you must drink much of the vodka, very fast, then no problem. Have good sleeping."

Thanks, big guy...

Our government-approved itinerary had us going to the capitol, Ashkabat, the next morning. When we woke up, though, Dima told us he was willing to change it. He offered to take us to a nomad village deep in the Karakum, a full day's off-road drive away, where he said we could catch a glimpse of Turkmen life as it had been a hundred years ago, and for centuries before that. The village was called 'Dan-La,' meaning 'Last Drop of Water,' but Dima simply called it the Capitol of the Desert. As he sun rose, we set off across the dunes.

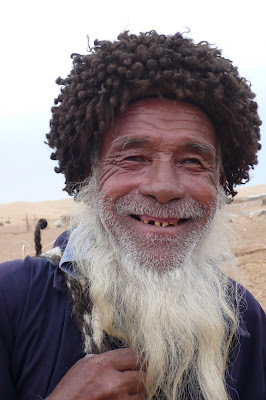

Master of the Desert

We drove all day over an inland sea of sand and rock, crossing mountainous dunes and dry lake beds smoother than the best asphalt. The desert seemed utterly empty, with only the occasional hawk, lizard or camel dotting the landscape. We went almost all day without seeing another vehicle, until we crested a steep rise in the dunes late in the afternoon. A motorcycle filled the windshield, and before anyone could react its rider was flying over the jeep. Fortunately, he landed in the soft sand without a scratch. As Murphy's Law predicts, the only two vehicles for a hundred miles had managed to drive straight into each other. The poor nomad's bike was in pretty bad shape, but after about an hour we managed to get it started, and he headed on his way.

Dima and the nomad discuss motorcycle maintenance

About an hour later, Dima pulled to a halt at the crest of a large hill. Below us in the golden afternoon light, we beheld Dan-La, Capitol of the Desert.

Dima is one of the few outsiders who ventures here, and his jeep is well-known. As a crowd of children gathered to greet us, we made our way down the slope and into the village.

Even after our months of travel, what we saw amazed us. Dan-La was a true time capsule, a forgotten world in the middle of a vast roadless expanse. Camels and donkeys wandered between the mud houses and nomad yurts. Women were busy weaving textiles by hand, while men sheared sheep with long knives in pens made of thorny branches. Children scurried about, waving their arms and shouting as they herded swarms of goats into their enclosures. An aging soviet truck and a few motorcycles were the only modern technology we saw.

Our host was the patriarch of the village's largest family, and welcomed us in his yurt with tea, bread and dried mutton. It was a dry year, and his two oldest sons had taken most of his goats and gone over a hundred miles to the north in search of better water and grazing. The life of the desert nomads, Dima explained, had been that way for centuries.

When our host heard about our crash with the motorcycle, he immediately declared that thanks must be given to Allah for the lack of injury or death. We chose a lamb from his pens, brought it to a special sacrificial post at the center of the village, and slit its throat. As the blood pooled in the sand, he lit a small fire on top of the blood, faced Mecca, and prayed in thanks to Allah. Like the pilgrims at Konye-Urgench, his offering was a blend of Islamic practice with ancient Animist and Zoroastrian traditions. As we would continue to see, Turkmenistan's Islamic religious identity is skin-deep, obscuring a much more complex and fascinating reality.

As the sun set, we gathered in the yurt for a feast of lamb, bread, tea and vodka. We discussed the price of goats in the Ashkabat markets and the likelihood of rain, told stories and bad jokes, and finally curled up under our blankets and drifted off to the bizarre howling of the camels tethered outside.

We woke just after dawn, to discover that the camels were somehow still howling. After a hearty breakfast of bread, tea and dried mutton, we joined the local women and children as they watered the camel herds at the village well.

Then, reluctantly, we began the long day's drive from the Capitol of the Desert across the Karakum to Ashgabat, where we discovered a capitol of a very different sort.

We emerged from the desert into a theme-park world of wide, empty avenues and gleaming marble buildings. Everywhere we looked the brilliant desert sunlight radiated from the golden face of the Great Turkmenbashi. High above the city, perched atop the "Arch of Neutrality," the Turkmenbashi's largest likeness rotates to always face the sun. Nearby stands his memorial to the great earthquake of 1948 which killed thousands and claimed the life of the infant despot's mother. The memorial is a massive statue of a great bull uprooting the earth with his horns while men and women scream grotesquely. Alone amid the chaos, the young Turkmenbashi is depicted as a golden infant unworldly in his serenity. He doesn't even need a diaper!

Among the Turkmenbashi's many gifts to his people, the Ruhnama is surely the greatest and most lasting. Known in English as The Book of the Soul, the tome is a rambling and often incoherent vision of the Turkmen people's history, ethos and place in the universe. Study of the book is required at all levels of Turkmen education and it is even part of the driver's license exam (the driving part, as any visitor will tell you, is much less important). After having his magnum opus translated into virtually every language on earth, the Turkmenbashi surpassed even himself by launching a copy into space. Since the Turkmenbashi's works are the only books available for purchase in Turkmenistan, we bought two copies.

Fortunately, there is another side to the Turkmen capitol. Ashgabat's Tolkuchka Bazaar is one of the greatest markets in Central Asia, and therefore the world. It stretches for miles, offering everything from camels and carburetors to German cars and Japanese plasma TVs.

With the battle-cry of a true market hound, Susannah twice led us into the chaos, camera poised and ready for some bare-knuckle bargaining.

After hours of admiring hand-woven carpets and antique silver earrings, Mike was loopy enough to don a traditional sheepskin hat.

Finally, our Central Asian adventures with deserts and dictators seemed to be at an end. We met Dima for our last ride together, west across the desert to the port city of Turkmenbashi, where we planned to take ship for Baku. We looked forward to a twelve hour sail across the Caspian and the comparative comforts of the Caucasus.

We were fools...